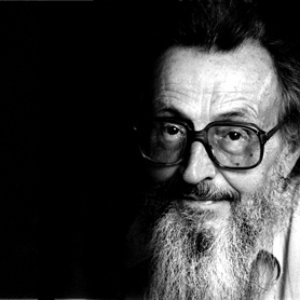

Biography

-

Born

3 December 1930

-

Born In

Paris, Île-de-France, France

-

Died

13 September 2022 (aged 91)

Jean-Luc Godard (born 3 December 1930) is a French filmmaker and one of the most influential members of the Nouvelle Vague, or "French New Wave".

Born to Franco-Swiss parents in Paris, he was educated in Nyon, Switzerland, later studying at the Lycée Rohmer, and the Sorbonne in Paris, where he studied ethnology. During his time at the Sorbonne, he became involved with the young group of filmmakers and film theorists that gave birth to the New Wave.

Known for stylistic implementations that challenged, at their focus, the conventions of Hollywood cinema, he became universally recognized as the most audacious and radical of the New Wave filmmakers. He adopted a position in filmmaking that was unambiguously political. His work reflected a fervent knowledge of film history, a comprehensive understanding of existential and Marxist philosophy, and a scholarly disposition that placed him as the lone filmmaker among the public intellectuals of the Rive Gauche.

The first and most celebrated period roughly spanned from his first feature, Breathless (1960), through to Week End (1967) and focused on narrative and somewhat conventional works that often refer to different aspects of film history. This cinematic period stands in contrast to the revolutionary period that immediately followed it, during which Godard ideologically denounced much of cinema’s history as "bourgeois" and therefore without merit.

Films

After seeing Orson Welles' Touch of Evil at the Expo 58, Godard was influenced to make his first major feature film, Breathless (1960), starring Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg. It was a seminal work of the French New Wave. It was a key determiner of the French New Wave's style, and incorporated quotations from several elements of popular culture — specifically American cinema. The distinct style of the film manifested in its numerous jump cuts, use of real locations rather than sets, and freedom from movie convention with character asides and broken eyeline matches. François Truffaut, who co-wrote Breathless with Godard, suggested its concept and introduced Godard to the producer who ultimately funded it, Georges de Beauregard.

The same year, Godard made Le Petit Soldat, which dealt with the Algerian War of Independence. Most notably, it was the first collaboration between Godard and Danish-born actress Anna Karina, whom he later married in 1961 (and divorced in 1967). The film, due to its political nature, was banned from French theaters until 1963. Karina appeared again, along with Belmondo, in A Woman Is a Woman (1961), which was in many ways an homage to the American musical. Karina desires a child, prompting her to leave her boyfriend, played by actor Jean-Claude Brialy, and seek out his best friend (Belmondo) as its father.

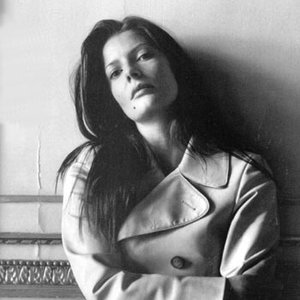

Anna Karina in Jean-Luc Godard's Vivre sa vie (My Life to Live)Godard's next film, Vivre sa vie (1962), was one of his most popular among critics. Karina starred as Nana, a mother and aspiring actress whose poor circumstances lead her to the life of a streetwalker. It is an episodic account of her trials. The film's style, much like that of Breathless, boasted the type of experimentation that made the French New Wave so influential.

Les Carabiniers (1963) was about the horror of war and its inherent injustice. It was the influence and suggestion of Roberto Rossellini that led Godard to make the film. It follows two peasants who join the army of a king, only to find futility in the whole thing as the king reveals the deception of war-administrating leaders.

His most commercially successful film was Contempt (1963), starring Michel Piccoli and one of France's biggest female stars, Brigitte Bardot. A coproduction between Italy and France, Contempt became known as a pinnacle in cinematic modernism with its profound reflexivity. The film follows Paul (Piccoli), a screenwriter who is commissioned by the arrogant American movie producer Prokosch (Jack Palance) to rewrite the script for an adaptation of Homer's The Odyssey, which German director Fritz Lang has been filming. Lang's "high culture" interpretation of the story is lost on Prokosch, whose character is a firm indictment of the commercial motion picture hierarchy. Another prominent theme is the inability to reconcile love and labor, which is illustrated by Paul's crumbling marriage to Camille (Bardot) during the course of shooting.

In 1964, Godard and Karina formed a production company, Anouchka Films. He directed Bande à part (Band of Outsiders), another collaboration between the two and described by Godard as "Alice in Wonderland meets Franz Kafka." It follows two young men, looking to score on a heist, who both fall in love with Karina, and quotes from several gangster film conventions.

Une femme mariée (1964) followed Band of Outsiders. Godard made the film while he acquired funding for Pierrot le fou (1965). It was a slow, deliberate, toned-down black and white picture without a real story. The film was entirely produced over the period of one month and exhibited a loose quality unique to Godard.

In 1965, Godard directed Alphaville, a futuristic blend of science fiction, film noir, and satire. Eddie Constantine starred as Lemmy Caution, a detective who is sent into a city controlled by a giant computer named Alpha 60. His mission is to make contact with Professor von Braun (Howard Vernon), a famous scientist who has fallen mysteriously silent, and is believed to be suppressed by the computer.

Pierrot le fou (1965) was one of his most cinematic pictures in terms of its complex storyline, distinctive personalities, and apocalyptic ending. Gilles Jacob, an author, critic, and president of the Cannes Film Festival, called it both a "retrospective" and recapitulation in the way it played on so many of Godard’s earlier characters and themes. With an extensive cast and variety of locations, the film was expensive enough to warrant significant problems with funding. Shot in color, it departed from Godard’s usual black and white minimalist works (typified by Breathless, Vivre sa vie, and Une femme mariée). He solicited the participation of Jean-Paul Belmondo, by then a famous actor, in order to guarantee the necessary amount of capital.

Masculin, féminin (1966), based on two Guy de Maupassant stories, La Femme de Paul and Le Signe, was a study of contemporary French youth and their involvement with cultural politics. An intertitle refers to the characters as "The children of Marx and Coca-Cola."

Godard followed with Made in U.S.A (1966), whose source material was Richard Stark's The Jugger; and Two or Three Things I Know About Her (1967), in which Marina Vlady portrays a woman leading a double life as housewife and prostitute.

La Chinoise (1967) saw Godard at his most politically forthright yet. The film focused on a group of students and engaged with the ideas coming out of the student activist groups in contemporary France. Released just before the May 1968 events, the film is thought to foreshadow the student rebellions that took place.

That same year, Godard made a more colorful and political film, Week End. It follows a Parisian couple as they leave on a weekend trip across the French countryside to collect an inheritance. What ensues is a confrontation with the tragic flaws of the over-consuming bourgeoisie. The film contains some of the most written-about scenes in cinema's history. One of them, a ten-minute tracking shot of the couple stuck in an unremitting traffic jam as they leave the city, is often cited as a new technique Godard used to deconstruct bourgeois trends. Week End's enigmatic and audacious end title sequence, which reads "End of Cinema," appropriately marked an end to the narrative and cinematic period in Godard's filmmaking career.

Politics

Politics are never far from the surface in Godard's films. One of his earliest features, Le Petit Soldat, dealt with the Algerian War of Independence, and was notable for its attempt to present the complexity of the dispute rather than pursue any specific ideological agenda. Along these lines, Les Caribiniers presents a fictional war that is initially romanticized in the way its characters approach their service, but becomes a stiff anti-war metonym. In addition to the international conflicts Godard sought an artistic response to, he was also very concerned with the social problems in France. The earliest and best example of this is Karina's potent portrayal of a prostitute in Vivre sa vie.

In 1960s Paris, the political milieu was not overwhelmed by one specific movement. There was, however, a distinct post-war climate shaped by various international conflicts such as the colonialism in North Africa and Southeast Asia. The side that opposed such colonization included the majority of French workers, who belonged to the French communist party, and the Parisian artists and writers who positioned themselves on the side of social reform and class equality. A large portion of this group had a particular affinity for the teachings of Karl Marx. Godard's Marxist disposition did not become abundantly explicit until La Chinoise and Week End, but is evident in several films — namely Pierrot and Une femme mariée.

Revolutionary period

The period that spans from May 1968 indistinctly into the 1970s has been subject to an even larger volume of inaccurate labeling. They include everything from his militant period, to his radical period, along with terms as precise as Maoist and vague as political. The term revolutionary, however, gives a more accurate impression than any other. The period saw Godard align himself with a specific revolution and employ a consistent revolutionary rhetoric.

Films

Amid the upheavals of the late 1960s Godard became interested in Maoist ideology. He formed the socialist-idealist Dziga-Vertov cinema group with Jean-Pierre Gorin and produced a number of shorts outlining his politics. In that period he travelled extensively and shot a number of films, most of which remained unfinished or were refused showings. His films became intensely politicized and experimental, a phase that lasted until 1980.

According to Elliott Gould, he and Godard met to discuss the possibility of Godard directing Jules Feiffer's 1971 surrealist play Little Murders. During this meeting Godard said his two favorite American writers were Feiffer and Charles M. Schulz. Godard soon declined the opportunity to direct; the job later going to Alan Arkin.

Jean-Pierre Gorin

After the events of May 1968, when the city of Paris saw total upheaval in response to the "authoritarian de Gaulle republic", and Godard's professional objective was reconsidered, he began to collaborate with like-minded individuals in the filmmaking arena. The most notable of these collaborations was with a young Maoist student, Jean-Pierre Gorin, who displayed a passion for cinema that grabbed Godard’s attention.

Between 1968 and 1973, Godard and Gorin collaborated to make a total of five films with strong Maoist messages. The most prominent film from the collaboration was Tout va bien, which starred Jane Fonda and Yves Montand, at the time very big stars.

Jean-Pierre Gorin now teaches the study of film at the University of California, San Diego and includes many of Godard's works.

The Dziga Vertov group

The small group of Maoists that Godard had brought together, which included Gorin, adopted the name Dziga Vertov Group. Godard had a specific interest in Vertov, a filmmaker and contemporary of both the great Soviet montage theorists, as well as the Russian constructivist and avant-garde artists such as Alexander Rodchenko and Vladimir Tatlin. Part of Godard’s evidently political shift after May 1968 was toward a proactive participation in the class struggle. Vertov’s films, particularly his most famous work, Man with the Movie Camera (1929), were very much centered on class struggles.

Later works

His return to somewhat more traditional fiction was marked with Sauve qui peut (la vie) (1980), the first of a series of more mainstream films marked by autobiographical currents: for example Passion (1982), Lettre à Freddy Buache (1982), Prénom Carmen (1984), and Grandeur et décadence (1986). There was, though, another flurry of controversy with Je vous salue, Marie (1985), which was condemned by the Catholic Church for alleged heresy, and also with King Lear (1987), an extraordinary but much-excoriated essay on William Shakespeare and language.

His later films have been marked by great formal beauty and frequently a sense of requiem — films such as Nouvelle Vague (New Wave, 1990), the autobiographical JLG/JLG, autoportrait de décembre (JLG/JLG: Self-Portrait in December, 1995), and For Ever Mozart (1996). Allemagne année 90 neuf zéro (Germany Year 90 Nine Zero, 1991) was a quasi-sequel to Alphaville but done with an elegiac tone and focus on the inevitable decay of age. During the 1990s he also produced perhaps the most important work of his career in the multi-part series Histoire(s) du cinéma, which combined all the innovations of his video work with a passionate engagement in the issues of twentieth-century history and the history of film itself.

Artist descriptions on Last.fm are editable by everyone. Feel free to contribute!

All user-contributed text on this page is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply.